Another Friday, another morning-after-the-night-before for Labour in local government byelections.

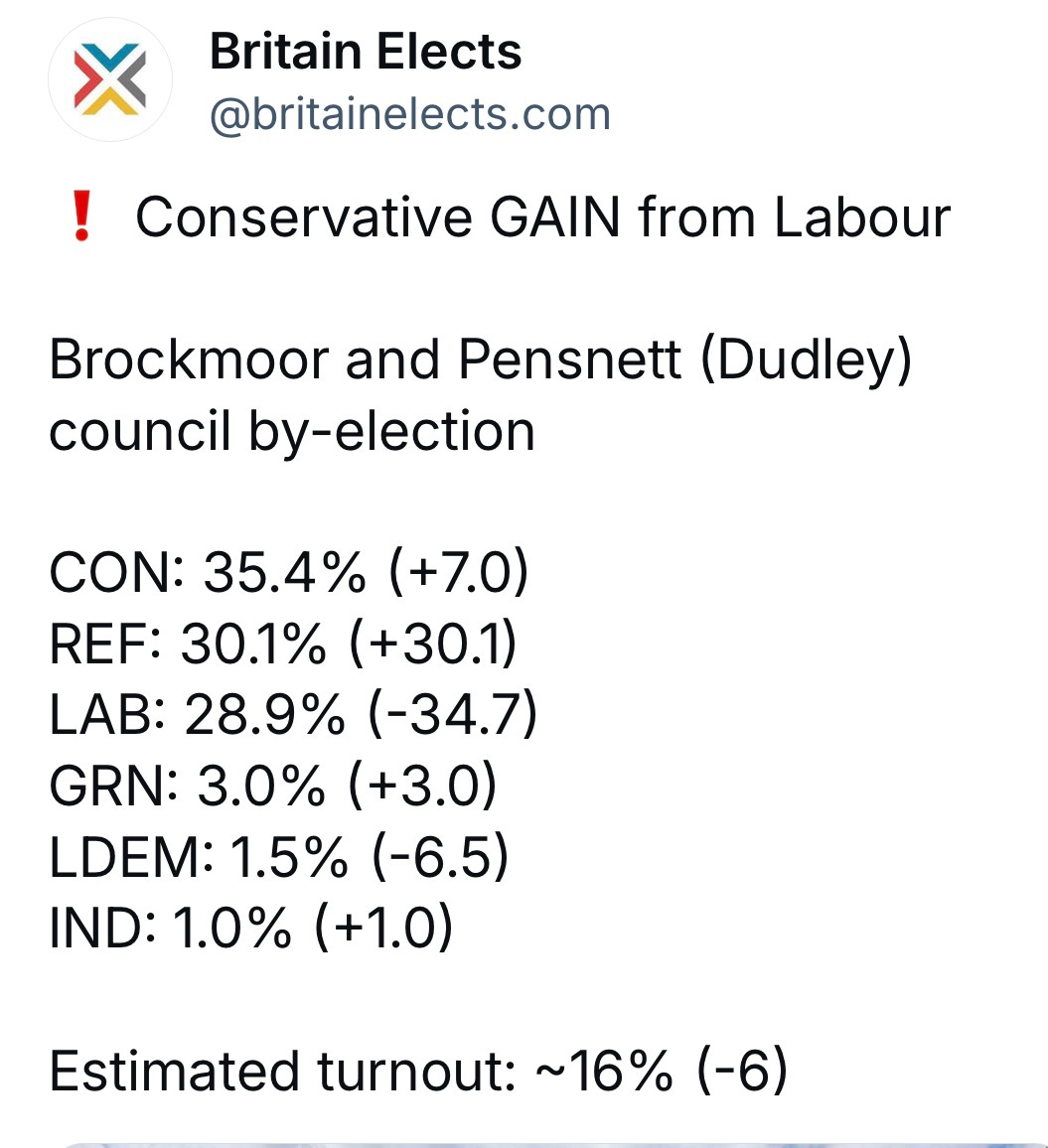

Last night in Dudley, Labour’s vote was down a massive 34.7 per cent in Brockmoor and Pensnett, pushing the party into third place behind a surging Reform – on 30.1 per cent – and the Tories who took the seat from Labour, up seven per cent to 35.4 per cent. And in Swale, Labour was down by over thirty points, smashed into third place behind Reform who took the seat from Labour with 33.9 per cent of the vote. In solid Labour West Thamesmead, Labour’s vote was still down 12.3 per cent – to 49.5 per cent – with turnout estimated to be a lowly 15 per cent.

Week after week it is the same story – a plummeting Labour vote, either with Labour holding on with much-reduced support, or outright defeat. The local collapse in support and morale reflects the overall national picture. Keir Starmer’s personal ratings have headed relentlessly downward for months. For Ipsos, latest research has just 27 per cent of the public satisfied with Keir Starmer’s performance, with 61 per cent dissatisfied. Public satisfaction with the government is also low, with a net satisfaction rating of -49.

Perhaps inevitably, but certainly very early on in the parliament, there is now speculation that Labour’s poor performance may mean that Keir Starmer will not survive as Labour leader and prime minister into the next election. That has come at the end of a terrible week in which Starmer’s work and pensions secretary, Liz Kendall, refused any compensation for the Waspi women, despite years of Labour politicians supporting a resolution of their cause and with the ombudsman having found maladministration in their case.

We are seeing that whilst a great deal of media noise was made over inheritance tax for farms, Labour’s biggest problems flow from the consequences of its policies for its own base of working class support.

As discussed many times before, Labour’s problems on domestic flow overwhelmingly from the adoption of a right-wing framework for its economic policy. This is the root cause of repeated ‘tough’ choices: rejection of the Waspi women, cancellation of pensioners’ winter fuel payments, rising student fees, increased bus fares, retention of the two-child benefit cap, and so on. Job cuts in the civil service and the announcement of the government’s recommendations on public sector pay are lining Labour up a confrontation with public sector workers. The government’s recommendation to the pay review bodies for a limit of a 2.8 per cent pay rise for thousands of public sector workers has already united the teaching unions in opposition, not least because it is unfunded, meaning it would have to come from existing budgets. As the NEU general secretary has argued, ‘austerity is ended in deeds not words.’

Labour has tied it itself up by refusing to raise necessary resources through taxation, relying on an argument that growth in the future will deliver a resolution to the country’s problems. Furthermore, by ruling out so many other tax options - such as on profit, income and wealth - Rachel Reeves stuck her tax rise on employers’ national insurance, a tax that rests on the number of people companies and charities employ. In doing so Starmer and Reeves gave the CBI a new pretext to oppose the measures contained in the Employment Bill. And on that panacea of growth, the OBR’s latest growth forecasts are woeful, and demolish any sense that the government is on course to deliver sustained high growth as a precursor to higher spending. Indeed, last week’s figures on GDP showing the economy had contracted for a second successive month demonstrate how far removed the economy is from a growth boom.

So Labour is stuck, the economics of the Labour right causing demoralisation that feeds the extreme right. Reeves’s ‘stability’ rules on bringing current spending into balance are extremely tight and will lead to cuts. The required departmental efficiency savings will cause considerable difficulty across the public sector. On welfare there is a very hard line developing in particular over work capacity assessments, which is likely to make the Liz Kendall who blocked the Waspi women seem positively benign. The full negative implications of the attack on the winter fuel payment are still to come but they are already enormous. And Reeves’s ‘stability’ rules are a big obstacle to action on climate change mitigation and adaptation (but not so inflexible that they cannot be stretched to include rising defence spending as a share of GDP).

Surveying its continually declining support the government has sought a reset. Clearly concerned about the implications of the defeat of Democrat incumbency in the US Starmer relaunched with six milestones, one of which is on household disposable income. It is correct to be concerned about spending power of the majority of the population. The ongoing squeeze on peoples’ living standards is a constant cause of public anger and frustration, and was the biggest issue for voters at the last election, despite Labour’s failure to address it in its manifesto. But a reset is meaningless with the present economic framework. In the government’s own budget documents the forecast is for an increase in real household disposable income (RHDI) per capita of just 1.4 per cent in 2024-25 and 1.1 per cent in 2025-26. It is forecast to rise by only 2.1 per cent over the forecast period as a whole. This means the government can meet its milestone of ‘higher living standards in every part of the United Kingdom by the end of the Parliament’ without actually significantly carrying out any noticeable improvement at all.

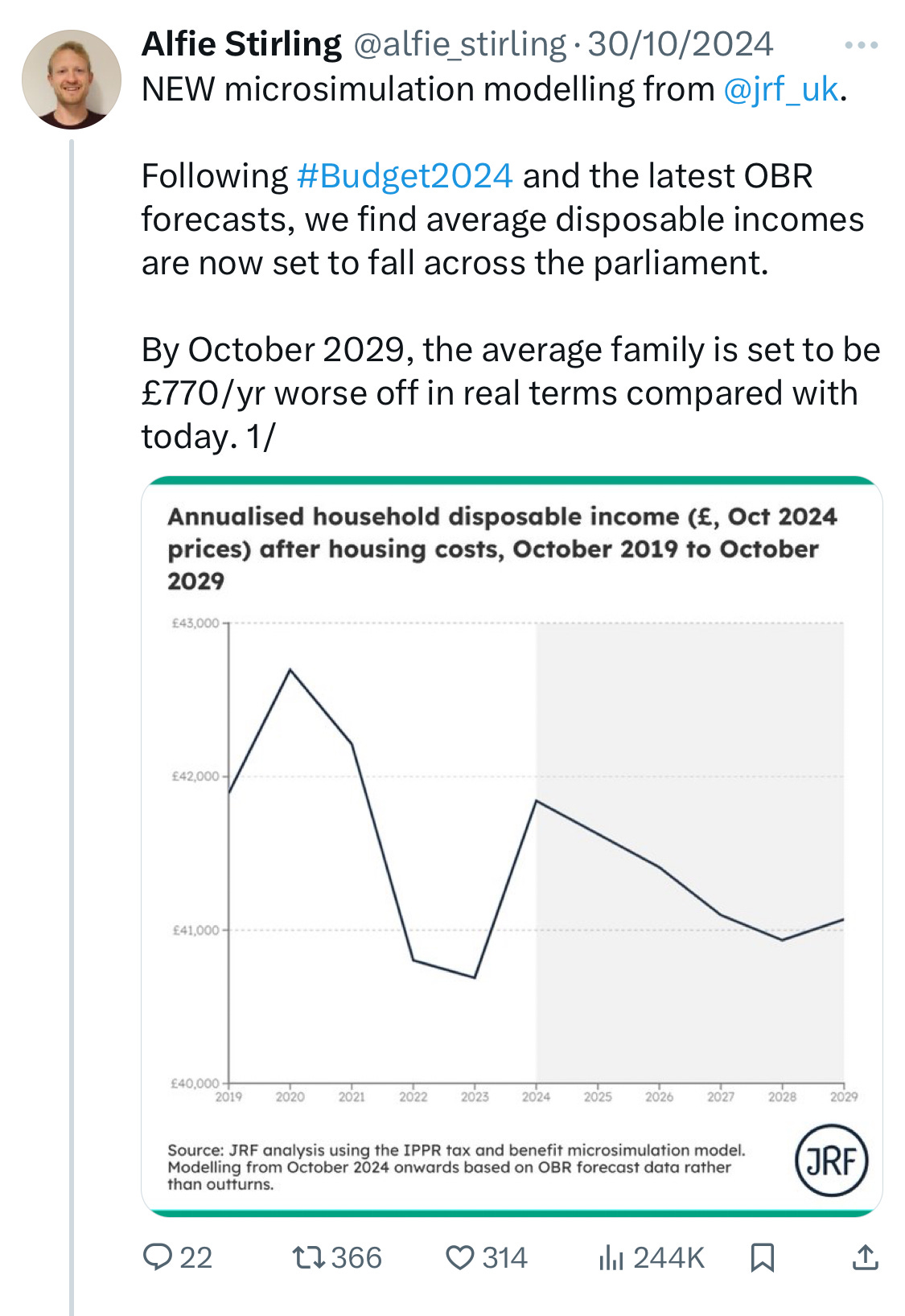

Moreover, Alfie Stirling, chief economist of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, has published microsimulation modelling based on the OBR’s forecasts that shows average disposable incomes actually set to fall across the parliament: ‘by October 2029, the average family is set to be £770/yr worse off in real terms compared with today.’ This is partly explained by real earnings growth set to slow, soaked up by rising housing costs and tax thresholds failing to rise with inflation. The JRF argues the OBR/government underestimate the true extent of the squeeze on living standards. Under this modelling, that the poorest third of households are set to see their real disposable incomes fall twice as fast as the highest income third – that is, relative poverty is set to rise.

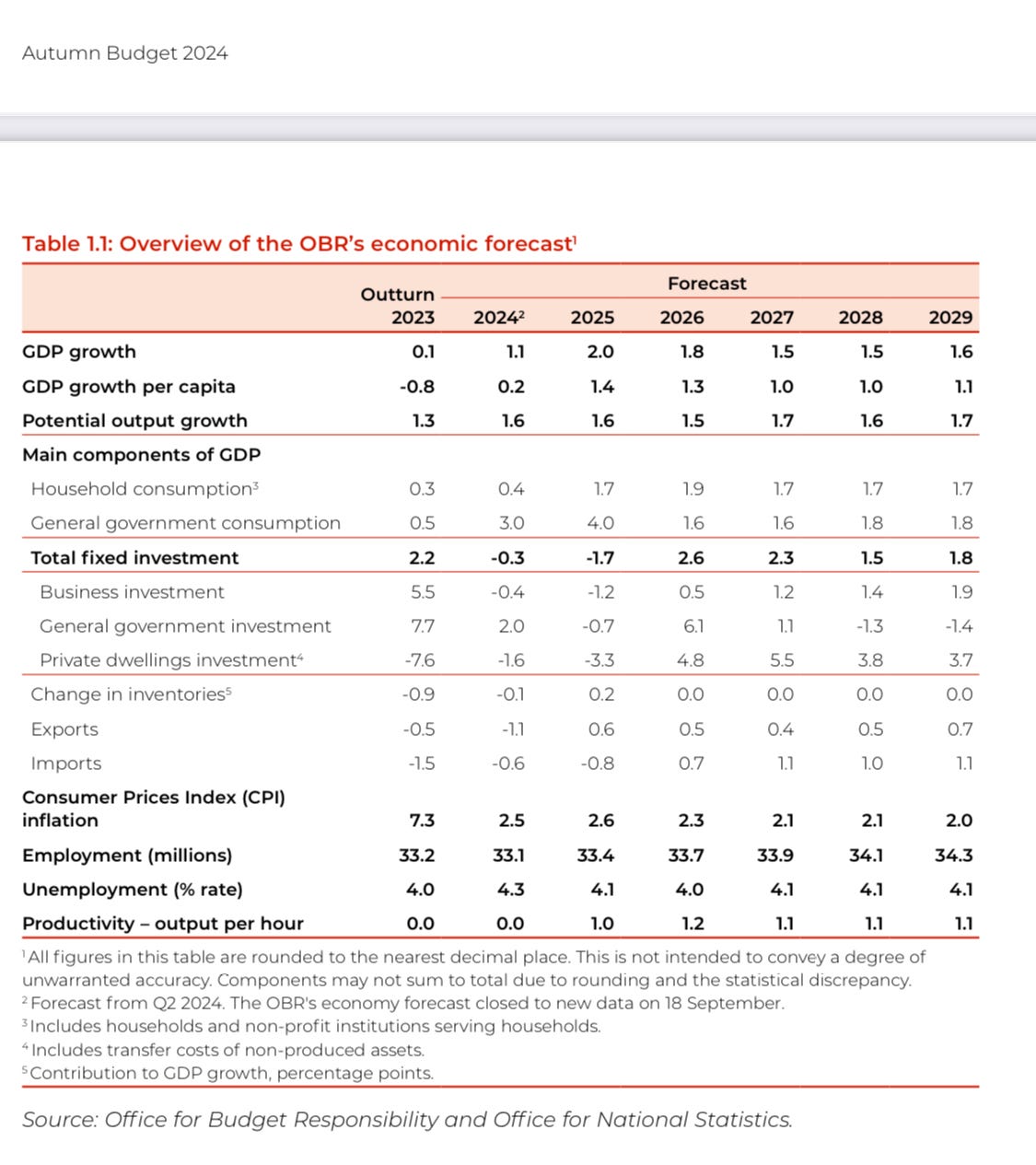

Nor can can Labour MPs confidently claim that the pain is all worth it because of longer-term gain. As the government’s own budget documents show, GDP growth is projected to be 1.1% in 2024; 2.0% in 2025; 1.8% in 2026; 1.5% in 2027; 1.5% in 2028; and 1.6% in 2029. This is extremely low.

At the same time, far from ending austerity, central government investment is projected to be falling at the end of this Parliament: up 2.0% in 2024; then -0.7% in 2025; +6.1% in 2026; +1.1% in 2027; -1.3% in 2028; -1.4% in 2029.

Starmer and Reeves are intent on standing on this ground: insufficient growth, actually falling central government investment by the end of the parliament, cuts in many services, still-squeezed household incomes, rising costs for many, a new attack on welfare - and so the economics of Labour’s right are paving the way for Reform to thrive.

Labour’s programme is on a doom loop that has to be strongly opposed within the labour movement. There is absolutely no point in wishing the government will improve - it is set on its course and that course has to be opposed in favour of the left’s alternatives. 2025 therefore needs to be the year that the left organises not only against the individual policy consequences of the government’s course, which of course it should do, relentlessly - but also actively in favour of the alternatives that show it is the left in society, not the extreme right, that offers the solutions to people’s problems.