‘The crisis that we inherit when we come to power will be the occasion for fundamental change and not the excuse for postponing it.’ Tony Benn, 1973‘It is not the inheritance we would have chosen, but it is the inheritance we will face if we are elected. It means we will not be able to announce additional investments under the green prosperity plan.’ Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves, 2024Introduction

Labour’s economic framework will generate a host of tensions and conflicts with its own base. The Reeves-Starmer recipe for the economy has moved Labour considerably to the right, particularly in the context of the scale of the problems facing the economy and British society. It lacks any major form of redistribution, or major measures to overcome inequality; it does not propose progressive changes to the tax system to increase the share of the burden on the richest to benefit working class people; it has a highly limited approach to public spending, and indeed polemicises against ‘tax and spend’, which it counterposes to growth. It has severely cut back its own green investment programme. With the main exception of public transport it makes no proposal to change the balance of ownership within the economy; and at a time of unprecedented squeeze on household incomes and with stagnant wages it has no target to grow the share of the economy going into wages or any immediate substantial measures to directly ease pressures on the cost of living.

Rarely has the disparity between the real situation and the programme of the leadership of the Labour party been more apparent.

What follows is not primarily a pure economic analysis, which is best provided by others. It focuses on (a) the problem of Labour’s approach to the day-to-day finances and living standards, such as the politics of cuts, public services and tax, and (b) the failure to match up to the need for major new public investment. In these two fields it is necessary to argue for a more far-reaching platform of measures to advance the interests of the majority of the population, both as pressure on the government itself, and as a left alternative to the hard right in both the Tory and Reform parties.

The following starts from the perspective that there are class interests in society. In order to act, it is necessary to work out the politics of those class interests as they are expressed through the actions of a government, in this case the incoming Labour government.

What is securonomics?

The main text summarising Labour’s outlook is Rachel Reeves’ Mais lecture (19/3/24), although its themes can be found a across a number of preceding statements such as for Labour Together and for the IPPR, and in her speeches and interviews.

Rachel Reeves calls her approach ‘securonomics.’ Reeves has situated securonomics within the ‘modern supply-side economics’ framework:

‘The Harvard political economist Dani Rodrik speaks of a new “productivist paradigm”. The US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has branded the Biden administration’s agenda “modern supply side economics”. Across the world, related ideas appear under different banners. I use the term “securonomics”.’[i]

Reeves aims for Labour’s economic policy to be seen as part of a trend or development within centre/centre-left thinking. Discussing that trend, the IPPR devoted the January 2024 edition of its Progressive Review, to ‘Modern supply side economics: A new consensus?’ In the opening editorial, the IPPR’s Joseph Evans argued that a ‘new consensus is developing in economic policymaking. After decades of market-based neoliberalism, this fresh consensus – variously described as modern supply-side economics, productivism, or ‘securonomics’ – is taking root on both sides of the Atlantic.’

Supply-side economics has usually been associated with the right, involving measures linked to tax cuts on higher earners and market deregulation, but for Evans at the IPPR, adherents of the ‘modern’ form of supply side economics define it is as recognising ‘that our economic problems are caused by over-reliance on market mechanisms and argues for greater use of the powers available to the state. Its advocates articulate how the levers of supply-side economic policy can be pulled to achieve progressive ends.’ In the US, Biden has said his perspective aims to ‘rebuild our economy from the middle out and the bottom up.’ Guardian economics editor Larry Elliott has described Reeves’ policy as believing that Labour can ‘deliver faster growth by working on the structural problems of the economy: reforming the planning system, boosting investment and improving skills.’[ii]

Reeves’ securonomics version of the supply-side trend has what she calls three pillars, which mean:

‘First, stability – the most basic condition for economic security and international credibility.

‘Second, investment – fostered through partnership, between dynamic business and strategic government.

‘And third, reform – to mobilise all of Britain’s resources in pursuit of shared prosperity.’

Reeves’ last pillar – reform – includes reform of the planning system and public services, as well as the labour market reforms and trade union legislation contained within the New Deal for Working People. To business, Reeves argues that the New Deal package is part of a shift towards labour markets that have the dynamism needed to power growth, helping workers move to higher productivity firms and higher productivity sectors.

Stability

Of Rachel Reeves’ three pillars, the first – stability – functions to motivate and defend stripping-out spending commitments, redistributive measures, or increased progressive taxation.

In the period running up to the general election campaign, Labour ruled out an increase in the top rate of income tax and any increase in corporation tax above twenty-five per cent. Measures such as the TUC’s proposal for a wealth tax have been rejected. It has leaned heavily on the argument that taxation in Britain is high – an argument that itself presents the incoming government with a self-inflicted constraint when facing billions of pounds of cuts in unprotected spending.

Stability is presented as essential to growth, and both Starmer and Reeves have argued for the need for growth before additional expenditure. In this form, the case for ‘growth first’ serves as a means to argue against a range of either tax rises or policies involving spending. For example, when asked whether Starmer’s pledge to increase the top rate of income tax had been ditched Reeves responded:

‘Yeah … I don’t see a route towards having more money for public services that is through taxing our way there.

‘It is going to be through growing our way there. And that’s why the policies that we’ve set out are all about how we can encourage businesses to invest in Britain.’[iii]

Unsaid however, is at what point the desired growth might open up the conditions for higher expenditure on public services, or other spending, and what that would be. (An exception to this is military spending, where Labour has said that ‘with Keir Starmer, Labour is committed to spending 2.5% of GDP on defence as soon as we can, and getting the best value for money for British taxpayers’).[iv]

Labour poses its fiscal rules as iron-clad and the foundation of stability. ‘Our fiscal rules are non-negotiable and will apply to every decision taken by a Labour government,’ the party says. ‘This means that the current budget must move into balance, so that day-to-day costs are met by revenues and debt must be falling as a share of the economy by the fifth year of the forecast.’

Labour’s version of stability also involves repetition of the falsehood that the credit card has been ‘maxed out.’ For the Labour leadership, stability stands as a polemic against measures for taxation, spending, and redistribution. So, a major feature of Labour’s self-limiting framework is its argument that as the Tories caused economic mayhem under Liz Truss there is now no money to be spent. Labour has rejected spending commitments and tax rises by blaming the Truss-Kwarteng budget, or in order to create a ‘business-friendly’ environment – or a mix of the two. Stability, ‘no money’ after Truss, and Labour’s fiscal rules are used as a package to justify deadening conditions on even quite mild social democratic policies. For example:

On refusing to give guarantees to plug the funding gap in local government, Keir Starmer said: ‘I can’t pretend that we could turn the taps on, pretend the damage hasn’t been done to the economy – it has,’ he said. ‘There’s no magic money tree that we can waggle the day after the election. No, they’ve broken the economy, they’ve done huge damage.’[v]

On Labour’s refusal to abolish the two-child benefit cap the Guardian reported that ‘shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, is said to have concluded it would be unaffordable due to the state of the economy.’[vi]

In the first week of the 2024 general election campaign Keir Starmer reaffirmed the retention of the two-child benefit cap when asked if Labour would abolish by claiming ‘we haven’t got the resources to do it at the moment.’[vii]

On Labour’s announcement that it will not reinstate a cap on bankers’ bonuses if it wins the next election, Rachel Reeves said: ‘as chancellor of the exchequer, I would want to be a champion of a successful and thriving financial services industry in the UK.’[viii]

On ruling out raising corporation tax above 25 per cent in the next parliament, Reeves said that ‘a 25% rate strikes the correct balance between the needs of our public finances and the demands of a competitive global economy’ and that the Labour government ‘will make the pro-business choice and the pro-growth choice.’

On public ownership of utilities: ‘Within our fiscal rules, to be spending billions of pounds on nationalising things, that just doesn’t stack up against our fiscal rules,’ Reeves told the Today programme.[ix]

Most dramatically, Labour eviscerated its own £28bn-a-year green prosperity plan, unveiled by Rachel Reeves in 2021. Originally involving Labour spending £28bn a year, Reeves and Starmer adjusted this down to £4.7bn a year, including slashing its warm homes programme. Justifying the cuts to the green prosperity plan, Starmer argued:

‘Liz Truss crashed the economy and other damage has been done. [Interest rates] are now very, very high – interest on government debt is already tens of billions of pounds a year.

‘We’ve always said we have to be within the fiscal rules and fiscal rules come first.’[x]

In a joint article, Starmer and Reeves based the green spending u-turn on the legacy of the Truss-Kwarteng budget, posing the situation as one that provides little room for manoeuvre. ‘None of us could have predicted the damage the Conservatives would do when they crashed the economy,’ they wrote, going on to argue: ‘It is not the inheritance we would have chosen, but it is the inheritance we will face if we are elected. It means we will not be able to announce additional investments under the green prosperity plan.’[xi]

Private bonanza, public risk

As has been shown, growth-first is key to Labour’s supply-side approach. Investment is repeatedly said to be a major factor in achieving Labour’s growth plan – one of Reeves’ three pillars. Under Starmer and Reeves, Labour has seen public investment as a means to lever in private investment in order to raise the level of investment in the economy as a whole. But with public investment plans such as the green investment package cut back, so Labour’s relative emphasis on private investment within the equation has risen further: Labour has placed increasing importance on the role of private sector investment as the remaining mechanism to stimulate growth. Labour Party rhetoric now rationalises its downgrading of public investment within the overall investment equation, reflecting the way it has been squeezed in Labour’s programme: ‘Public investment is one important lever available to governments, with the potential to crowd in private investment. But it is only one lever, and it must be used judiciously.’[xii]

With public investment held back in relative terms, to be used ‘judiciously’, it has taken on the role as a facilitator for private capital. Labour intends to unlock private investment via its National Wealth Fund. Capitalised with £7.3 billion over the course of the new parliament the fund will have a remit to support Labour’s growth and clean energy missions, ‘making transformative investments across every part of the country.’ Reeves and Starmer have been clear that the fund will have a target of attracting three pounds of private investment for every one pound of public investment.[xiii]

To create the conditions for Reeves’ invitation to the private sector, planning reform will be used to make investment attractive to business. In her Mais lecture Reeves described the planning system as ‘the single greatest obstacle to our economic success.’ As that statement demonstrates, reform of the planning system now carries extraordinary weight within Labour’s economic programme. For the Labour front bench, absolutely massive expectation rests on planning reform.

The Labour leadership continued to pursue its co-ordination with big business during the election campaign itself, meeting with the ten biggest private investment groups at the headquarters of M&G, the global fund manager. Attendees of Labour’s British Infrastructure Council include representatives from BlackRock, Lloyds Banking Group, Santander, HSBC, Phoenix Group and Fidelity International, among others. ‘It is these businesses, not taxpayers, that a Labour government hopes will pay for much of what it wishes to do’, the Times’ Patrick Maguire reported.[xiv] This latter point should be noted – Labour hopes to solve the problems of the public finances not through taxation but through its supply side agenda of boosting growth. Bloomberg has reported that the aim of a agreeing a huge programme of new private investment involves ‘a surge that the opposition party hopes is large enough to help meet its ambitious growth goals and avoid sweeping tax hikes if it wins next week’s election.’[xv]

And according to Bloomberg’s report, Labour’s plan involves ‘considering how the government can take on some of the risk of private investments in key projects.’

Thus, Labour is working closely with business to utilise public money so that the state assists the private sector make large profits. Effectively it is a plan drawn up directly with big capital. Labour now ‘believes in the sagacity of private capital, and thinks it will unleash growth through financial orthodoxy and deregulation,’ as David Edgerton has written.[xvi] An eve-of-poll report for the Guardian found one insider with knowledge of the party’s growth plan who said there could be ‘pretty hair-raising stuff’ ahead. ‘There will have to be almost Truss-ite deregulation, on things like planning and freeports, in the first two years, that will have to be balanced with the longer term. But it will have to be presented carefully so that it doesn’t look like Tory-lite, sugar-rush economics.’[xvii]

One Labour official joked to Bloomberg ‘that the party would be getting BlackRock to rebuild Britain.’[xviii]Indeed, this sums up how political dynamics will start to apply themselves. Economics professor Daniela Gabor has argued that ‘the choice here is not merely between public and private financing of public goods, but whether British citizens should tolerate the government handing out public subsidies for privatised infrastructure.’ Politics – who stands to gain - will be played out through this process, affecting labour movement politics including into the Labour Party. Unite the Union has repeatedly shown the scale of the problem of profiteering by business. Ifsuccessful on its own terms Labour’s plan means a bonanza for shareholders and the richest, not least since it comes without the promise of any direct redistribution flowing from the arrangement: no increase in corporation tax, no new taxes such as on dividends, no increase in the top rate of income tax. This is really what Rachel Reeves meant when she said that under Starmer and Reeves ‘Labour will be more pro-business than Tony Blair’.[xix]

It is obvious that the scenario Labour envisages will form a new terrain for competing class and social interests to be expressed. Its plans will involve the private sector seeking to maximise profits and payments to shareholders; and on the other side pressure for wage increases, for progressive redistributive taxation, or for action over corporate profiteering and unaccountable behaviour, or all of these. That includes the need for new taxation such as on wealth.

Investment is key

Investment in the British economy is abysmally low. Consequently, higher investment is vital. According to the Resolution Foundation, in the forty years to 2022 total fixed investment in the UK averaged 19 per cent of GDP, the lowest in the G7 group of countries.[xx] The foundation has argued that virtually all of the productivity gap with France is explained by French workers having more capital to work with.[xxi]

It is absolutely correct to say that private sector investment is low in Britain. UK companies have invested twenty per cent less than those in the US, France and Germany since 2005, placing Britain in the bottom 10 per cent of OECD countries.[xxii]However it is false to counterpose the question of private sector investment to the importance of raising the level of public sector investment, by downplaying the latter.

The Resolution Foundation’s major report, ‘Ending Stagnation’ (2023), showed that the average OECD country invests nearly 50 per cent more than the UK:

‘In OECD advanced economies, the average amount of public sector investment is 3.7 per cent of GDP a year, nearly 50 per cent more than in the UK. And our low public investment norm is persistent: we have been in the weakest third of OECD countries for three in every four years this century. Had OECD average levels of public investment prevailed over the past two decades, we would have invested around £500 billion more.’ [xxiii]

As the report stated, although the majority of investment is made in the private sector, ‘public investment matters too. It accounts for a fifth of total investment in the UK and dominates in some critical sectors – from transport infrastructure to health – and in poorer places.’[xxiv] Consequently, the foundation’s report argued that Britain needs to become a ‘normal investor’ – that ‘public investment of 3 per cent of GDP would step us up to the OECD average.’ Such a level is outside the bounds of what Labour has proposed.

In the final week of the general election campaign a group of sixty-five economists and academics released a statement as part of the Invest in Britain campaign, saying that the UK has ‘consistently seen some of the lowest levels of public investment in the G7, and has been well below the OECD average for public investment.’[xxv]

Recent IPPR analysis by George Dibb and Carsten Jung, published during the British general election campaign, found that within the dataset it studied, the UK has never been at or above the G7 median for public investment.[xxvi]

But despite all this, the IFS warned in January that public sector net investment is currently set to fall as a share of GDP over the next parliament.’[xxvii] As Dibb and Jung have emphasised, despite the wide ranging acceptance of its economic benefits, and notwithstanding the UK’s position at the bottom of the G7 league table, ‘both Conservative and Labour parties plan to further reduce public investment over the next parliamentary term.’ Their report noted of Labour’s plans:

‘Current OBR forecasts based on the government’s plans, last updated at the March 2024 budget, see public investment falling, not increasing, after the election. The Labour party has pledged to invest a further £4.74 billion per annum (raised through tax changes and borrowing) (Labour 2024) as part of its revised Green Prosperity Plan but the forthcoming cuts pencilled in by the government are so severe that even if Labour’s plans are added on, public investment would still be declining over the next parliament.’[xxviii]

The weakness of the Labour Party’s position on public investment so massively knocks into Reeves’ investment pillar that it deprives it of a huge driver to overcome a profound weakness of the British economy - which is in turn a significant cause of a whole range of social and economic problems facing the British working class and British society. The results of Britain’s longstanding problem of underinvestment can be seen all around us. ‘UK hospitals have fewer beds per capita than all but one of the OECD advanced economies, and fewer MRI machines than all but four. Our economy is held back by poor transport links and traffic congestion: UK workers spend more time commuting than those in all but two OECD countries.’[xxix]

On the central question of the long-term failure of the British economy - underinvestment - Labour goes into government with wholly inadequate approach to the need to rapidly raise public investment.

There is some movement around the proposal to raise the level of public investment. For example, Larry Elliott has argued in the Guardian that ‘a Labour government should commit to investing a minimum of 3.7% of GDP – the average for the OECD nations – each year to state capital spending, with no strings attached. If the fiscal rules are an obstacle to a sustained, guaranteed flow of investment spending, then change the fiscal rules.’[xxx] As noted earlier, the Resolution Foundation has proposed raising public investment to around 3 per cent. Socialist Economic Bulletin has argued for many years – in fact decades - for raising investment.[xxxi]

Given the line Labour has taken on public and private investment, a central question is the degree to which pressure can be built for raising the level of public investment in the economy – alongside the redistributive policies necessary to raise living standards and improve the position of the majority of the population.

Labour, tax and spend

Whilst Labour views its approach as a two-term project, there is already a massive looming crisis facing the public sector with a new round of austerity amounting to billions of pounds.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has criticised both of main parties for ‘avoiding the reality that they are effectively signed up to sharp spending cuts, while arguing over smaller changes to taxes and spending.’[xxxii]

Before the election was called, Paul Johnson of the IFS complained in March[xxxiii] that Labour and the Conservatives are joining in ‘a conspiracy of silence in not acknowledging the scale of the choices and trade-offs that will face us after the election’ which included ‘eye-wateringly tough choices’ on public service spending.

Despite weeks of campaigning, the conspiracy of silence held.

The immediate crisis for public services is that the Tories’ spring budget included an increase in day-to-day government spending at one per cent above inflation every year until 2029. Since some departments – such as health or defence - have protected budgets, the one per cent increase overall means other unprotected areas of expenditure face huge cuts. Consequently, both Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have repeatedly faced questions from the media about what they intend to do about cuts to unprotected budgets. They have given no commitments to halt the cuts.

IFS figures state that the cuts would require a spending top-up in 2028–29 of £10–20 billion to be avoided.[xxxiv] When asked on Kuenssberg, rather than providing guarantees about cuts or indeed even increases in spending, Rachel Reeves answered in broad terms[xxxv]. ‘There's not going to be a return to austerity under Labour’, she said. When pressed she only replied that ‘I don't want to make cuts to public services.’

Labour’s self-imposed position on the funding of public services to systematically rule out the key revenue-raising mechanisms such as rises in income tax, corporation tax and National Insurance. (Labour has also rejected a rise in VAT, which is positive since it is regressive).

Ed Balls, the former shadow chancellor, has warned that Rachel Reeves would ‘box herself in quite a lot’ on tax. ‘The more commitments you make on tax in opposition,’ he has argued, ‘the harder it is to govern when you’re there. And she’s definitely making her task more difficult.’[xxxvi]

The publication of Labour’s manifesto provoked greater focus on the party’s plans for the public finances. The IFS’s Paul Johnson wrote in response to the manifesto:

‘On current forecasts, and especially with an extra £17.5bn borrowing over five years to fund the green prosperity plan, this leaves literally no room – within the fiscal rule that Labour has signed up to – for any more spending than planned by the current government. And those plans do involve cuts both to investment spending and to spending on unprotected public services. Yet Sir Keir Starmer effectively ruled out such cuts. How they will square the circle in government we do not know.’[xxxvii]

The IFS called the spending increases offered by Labour’s manifesto as ‘tiny, going on trivial:’

‘The public service spending increases promised in the “costings” table are tiny, going on trivial. The tax rises, beyond the inevitable reduced tax avoidance, even more trivial. The biggest commitment, to the much vaunted “green prosperity plan”, comes in at no more than £5bn a year, funded in part by borrowing and in part by “a windfall tax on the oil and gas giants”.

‘Beyond that, almost nothing in the way of definite promises on spending despite Labour diagnosing deep-seated problems across child poverty, homelessness, higher education funding, adult social care, local government finances, pensions and much more besides. Definite promises though not to do things. Not to have debt rising at the end of the forecast. Not to increase tax on working people. Not to increase rates of income tax, National Insurance, VAT or corporation tax.’

From this, the FT’s Martin Wolf wrote that Labour’s manifesto constituted ‘the politics of evasion.’

Looking at the prospect of cuts, in response to the Labour manifesto, Alfie Stirling of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation calculated that ‘around £2bn of the additional £5bn of spending on public services will go to unprotected departments. So the planned cuts to those departments would be around 10% smaller under a Labour government.’[xxxviii] That is, still big cuts, to already under-funded departments. James Meadway has stated that a ‘total increase in public service spending of £4.5bn is dwarfed by the £20bn of annual cuts currently scheduled for the next parliament.’[xxxix]

Moreover, where Labour has sought to offer change for the public services, such as on the NHS, this too is encased in a financial straitjacket. So, as Meadway has put it of Labour’s costings, ‘an extra £2.5bn is earmarked for the NHS and healthcare: to put this in context, the repair bill alone for the NHS comes to £12bn.’[xl]

Having closed down the most obvious big revenue-raising routes available, the politics of Labour’s spending squeeze shifted in the weeks before polling day onto a debate about other options, in pursuit of squaring the circle of the impending cuts. The Guardian’s City Editor Anna Isaac reported in June that Labour is considering options for changes including to inheritance tax or capital gains tax, although a Labour spokesperson was quoted as saying that ‘nothing in our plans requires any additional tax to be increased.’[xli] (The Guardian’s political editor Pippa Crerar reported last August[xlii] that Reeves would not increase capital gains tax, amongst other options). The New Statesman’s George Eaton also speculated about the possibility of a rise in capital gains tax, reporting from Rachel Reeves’ q&a on the 11th of June that she declined opportunities to rule out an increase in CGT, merely stating that Labour has ‘no plans’ to raise it.[xliii] Also at the New Statesman, Andrew Marr aired the proposal from Chris Giles in the Financial Times for ‘tiering reserve remuneration for banks holding money overnight at the Bank of England.’[xliv]This would, as Marr reports, mean changing the Bank of England’s rules to cut the interest it pays and ‘could free up around £23bn a year.’[xlv]

Some commentators discussed whether Labour will proceed with a review of council tax, but Labour moved quickly to shut down speculation of a revaluation of council tax.

And so on. The hunt for an alternative to a new round of cuts in the public services is a direct product of the vacuum left by Labour.

By ruling out the main progressive forms of taxation for an entire parliament Labour has both shut down key mechanisms for revenue-raising and direct redistribution, and limited the scale of what it is prepared to do programmatically. That explains Labour’s consistent refusal to abolish the two-child benefits cap, for example, even with the weight of evidence in favour of abolition.

Despite the reports and questioning, Labour has made no commitment to make up the shortfall facing public spending, and repeatedly counterposed growth to tax-and-spend. Labour’s manifesto has made no commitment to resolve the chronic problems of the public services, what Andrew Fisher has called ‘austerity baked in.’[xlvi]

Consequently, opposition to cuts will sharpen for as long as Labour does not change tack.

The deeper shortfall

However, there is a deeper shortfall than even the impending situation in the public services.

A report by the Centre for Progressive Policy[xlvii] (November 2023) calculated that the next government will need to spend an additional £142bn per year by 2030 (equivalent to a 1.56 per cent increase in public spending per year) just to maintain current levels of public services. That is in addition to finding the £19billion due to be lost from unprotected spending.

John McDonnell and Andrew Fisher produced a detailed summary of the problems facing public services and the costs associated with meeting these last October. On their figures, just to reverse austerity cuts and deliver modest expansions is likely to be in excess of £70 billion extra in day-to-day spending, (which they say is an underestimate).[xlviii]

Pressures are to be found everywhere. To take education, the National Education Union has argued that education funding in England currently stands at 4.19 per cent of GDP and that it would take an investment of £20.3bn to lift education spending back to the OECD average of 5 per cent. NEU general secretary Daniel Kebede pointed out last September that whilst the DfE calculated that around £5.3 billion a year was required to maintain school buildings and deal with the most serious risks, the Treasury allocated only around £3.1 billion, more than 40 percent below the amount civil servants judged necessary.[xlix]Difficulties such as this in education are replicated across the public sector.

Whichever figures are used, the damage of years of austerity in the public services is huge.

Public sector problems extend to staff levels and pay. Recruitment and retention in the public sector are currently hampered by years of real-terms cuts in pay. The recent surge in industrial action underlined the severe difficulties over pay and conditions faced by workers in both private and public sectors.

A need for more resources to fund the programme of a Labour government is reflected in the views of think tanks and policy analysts. In his balanced view of the Labour manifesto, George Dibb of the IPPR praised the document for its big commitments and ‘the scale of Labour’s aspiration.’ However, Dibb also argued that Labour needed to ‘go beyond the rhetoric of the manifesto and noticeably improve people’s lives. This means…most prominently finding the funding to not just reverse the government’s cuts but increase spending and investment over a first term.’[l]

Terms of the debate are too small

While much of the discourse around Labour’s programme is dominated by an argument about why Labour should be pressed to protect already too low spending from further cuts, at the same time there is a huge backlog of demands for additional government expenditure – such as over the two child cap, free school meals, and dire local council finances. Even if Labour were to find revenue-raising measures and loopholes to plug the much-discussed gap for day-to-day spending – which it has not done - that would still go nowhere near the pent-up need for expansion of public services after fourteen years of austerity, and beyond that, bigger social transformation. That is, the terms of the debate are too small, and consequently are likely to crack under pressure. Climate change is moving faster and more dangerously than at any time and will require more, not less, investment than that envisaged, as successive climate crises disrupt ‘stability’ and politics-as-usual.

The politics of this for the left mean of course to oppose impending cuts, but also to press for a wider expansion of public services to end the consequences of austerity - including with the necessary progressive revenue-raising on wealth and the richest that requires.

A decade of national renewal

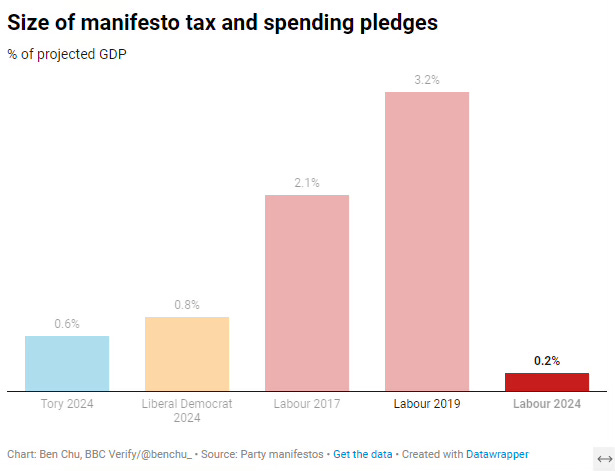

To see the limited scale of what Labour’s manifesto has to offer, the BBC’s Policy and Analysis correspondent, Ben Chu, calculated that the 2024 Labour manifesto’s fiscal package (tax rise/spending pledges) amounts to around 0.2% of GDP.[li] That compares to 2.1 per cent in Labour’s 2017 manifesto - and even 0.6 per cent in the present Tory manifesto. That is what was meant by tiny, going on trivial.

The limited terms of Labour’s manifesto commitments on taxation and expenditure form part of the party’s wider economic policy: securonomics is consciously counterposed to ‘tax and spend.’[lii] As discussed, in its hierarchy of priorities Labour places stability above all else - a version of stability that provides a deadening effect on measures for widespread social reform. Labour has openly argued that it requires two terms: ‘a decade of national renewal.’ In limiting its programme and simultaneously arguing that its objectives require at least a two-term timeframe, Starmer and Reeves warn that they will make decisions that will run counter to the expectations of the Labour Party’s base. Writing for the Telegraph Keir Starmer argued in December 2023 that there ‘will be many on my own side who will feel frustrated by the difficult choices we will have to make.’[liii] The leadership has been issuing warnings of this nature for some time. In his 2022 Labour conference speech Starmer told delegates that ‘we have to be honest. I would love to stand here and say Labour will fix everything. But the damage they’ve done – to our finances and our public services means this time the rescue will be harder than ever. It will take investment – of course it will. But it will also take reform.’[liv]

Problems associated with Labour’s two term approach are glaringly obvious to observers across the political spectrum. The Spectator’s political editor Katy Balls, writing in The i paper, concluded that ‘one of the reasons Starmer and his Shadow Cabinet keep talking about a “decade of renewal” is a concern that they will be so restrained financially in the first term, they won’t be able to do much. Hence the need to lower expectations and not make big pledges.’[lv] A commitment to a ten-year programme has an inbuilt tension with a five-year parliamentary cycle and even shorter timeframes for elections during that five-year period. George Dibb at the IPPR for Labourlist, recently called for steps to increase spending and investment over the first term:

‘Why a first term? Because as the anticipated swing from Johnson in 2019 to Starmer in 2024 shows, voters don’t have the patience to wait ten years to see these promises delivered.’[lvi]

Whilst in opposition the language of a decade of national renewal can provide a technocratic sheen, in government it will quickly become a mechanism for telling people to wait. A Labour government elected without a major programme for substantial change in living standards risks opening the door to the populist hard right. The political dynamics built into that are that the fight for more rapid and substantial change will be both directed towards the Labour government, and as an alternative in opposition to the solutions of the hard right under the Tories and Reform.

Summary

The Labour government will introduce some measures that will enjoy some support in the labour movement and beyond. However, Labour’s position is inadequate to the scale of problems faced by the majority of the population and does not sufficiently address the most fundamental problems of British society, ie those associated with longstanding under-investment. At present it does not have an answer to the most urgent threat of cuts.

Even if its alliance with big capital were successful within the terms Labour has set itself, by forcing people to wait for the consequences of private sector-led growth over the course of a decade, with public services still on their knees from austerity, Labour risks opening the door to the populist hard right to exploit disaffection.

For the left and the unions that means to oppose cuts, and pushing for an expansion of funding for public services to turn around years of austerity. It also means to fight for redistribution and a programme of measures to raise disposable household incomes. It involves campaigning for progressive revenue-raising measures including on wealth and incomes in order to deliver on these objectives; and significantly raising public investment as a proportion of the economy, not only to raise the living standards of the majority but as the means to confront the climate crisis.

[i] Mais lecture https://labour.org.uk/updates/press-releases/rachel-reeves-mais-lecture/

[ii] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/mar/20/rachel-reeves-economic-growth-reform-planning-investment

[iii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/aug/27/rachel-reeves-rules-out-wealth-tax-if-labour-wins-next-election#:~:text=The%20shadow%20chancellor%20confirmed%20that,of%20what%20we've%20said.

[iv] https://labour.org.uk/updates/stories/labours-defence-policy-how-we-will-provide-strong-national-defence-for-britain/#:~:text=With%20Keir%20Starmer%2C%20Labour%20is,for%20money%20for%20British%20taxpayers.

[v] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2024/mar/28/starmer-says-he-cannot-turn-the-taps-on-to-fix-crisis-in-council-funding

[vi] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/jul/16/labour-keep-two-child-benefit-cap-says-keir-starmer

[vii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/live/2024/may/24/keir-starmer-rishi-sunak-uk-general-election-2024-labour-conservatives?page=with:block-665036dc8f0891c9817ac631#block-665036dc8f0891c9817ac631

[viii] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/jan/31/labour-party-cap-bankers-bonuses-financial-services

[ix] https://labourlist.org/2022/07/nationalisation-just-doesnt-stack-up-against-our-fiscal-rules-reeves-says/

[x] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2024/feb/08/labour-cuts-28bn-green-investment-pledge-by-half

[xi] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/08/labour-28bn-green-prosperity-plan-keir-starmer-rachel-reeves

[xii] Rachel Reeves, Mais lecture https://labour.org.uk/updates/press-releases/rachel-reeves-mais-lecture/

[xiii] https://labour.org.uk/change/kickstart-economic-growth/#boosting-investment

[xiv] https://www.thetimes.com/comment/columnists/article/reevess-plan-for-growth-is-built-on-private-cash-0w0sqpqvg

[xv] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-06-27/labour-expects-billions-of-private-investment-after-uk-election

[xvi] https://amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/jun/28/keir-starmer-labour-britain-conservative-party

[xvii] https://amp.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/jul/03/no-drama-starmer-how-labour-would-govern

[xviii] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-06-27/labour-expects-billions-of-private-investment-after-uk-election

[xix] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/rachel-reeves-labour-business-tony-blair-9chlj9q0g

[xx] https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/uncategorized/executive-summary/

[xxi] https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/uncategorized/executive-summary/

[xxii] https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/reports/ending-stagnation/

[xxiii] https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Ending-stagnation-final-report.pdf

[xxiv] https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Ending-stagnation-final-report.pdf

[xxv] https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/sunak-starmer-economist-boost-investment-3140399

[xxvi] https://ippr-org.files.svdcdn.com/production/Downloads/Rock_bottom_June24_2024-06-18-081624_arsv.pdf

[xxvii] https://x.com/theifs/status/1750440393525563657?s=46

[xxviii] https://ippr-org.files.svdcdn.com/production/Downloads/Rock_bottom_June24_2024-06-18-081624_arsv.pdf

[xxix] https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Ending-stagnation-final-report.pdf

[xxx] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/13/britains-economy-three-manifesto-pledges-labour-must-make

[xxxi] https://socialisteconomicbulletin.net

[xxxii] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/labour-tories-spending-cuts-general-election-b2556526.html#

[xxxiii] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-68498937

[xxxiv] https://ifs.org.uk/articles/how-should-we-interpret-parties-public-spending-pledges-election

[xxxv] https://x.com/FisherAndrew79/status/1794650240383156401

[xxxvi] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/feb/01/labour-rules-out-raising-corporation-tax-above-25-in-next-parliament

[xxxvii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/live/2024/jun/13/general-election-labour-manifesto-keir-starmer-rishi-sunak-conservatives-plaid-cymru?page=with:block-666ae9378f08b0b758d2aa8e#block-666ae9378f08b0b758d2aa8e

[xxxviii] https://x.com/alfie_stirling/status/1801204383968878852

[xxxix] https://novaramedia.com/2024/06/13/labours-slippery-manifesto-offers-no-end-to-austerity/

[xl] https://novaramedia.com/2024/06/13/labours-slippery-manifesto-offers-no-end-to-austerity/

[xli] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/jun/21/labour-drafts-options-for-wealth-taxes-to-unlock-funds-for-public-services

[xlii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/aug/27/rachel-reeves-rules-out-wealth-tax-if-labour-wins-next-election

[xliii] https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2024/06/is-labour-guarding-real-tax-plans-rachel-reeves-capital-gains

[xliv] https://x.com/ChrisGiles_/status/1798740957992796285

[xlv] https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/labour/2024/06/what-historic-labour-keir-starmer-win-mean-britain-election-andrew-marr

[xlvi] https://inews.co.uk/opinion/labour-manifesto-return-austerity-keir-starmer-3107975

[xlvii] https://www.progressive-policy.net/publications/funding-fair-growth

[xlviii] https://labouroutlook.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Labour-In-Tray-Report-Final.pdf

[xlix] https://tribunemag.co.uk/2023/09/in-britain-everything-is-crumbling

[l] https://labourlist.org/2024/06/labour-manifesto-2024-ming-vase-strategy-policies-growth-net-zero/

[li] https://x.com/BenChu_/status/1801202947860103353

[lii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/jun/23/rachel-reeves-changing-britain-shadow-chancellor-interview

[liii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/dec/02/keir-starmer-praises-margaret-thatcher-for-bringing-meaningful-change-to-uk

[liv] https://modernleft.substack.com/p/notes-on-keir-starmers-speech

[lv] https://inews.co.uk/opinion/rishi-sunak-keir-starmer-shared-experience-ifs-3129420

[lvi] https://labourlist.org/2024/06/labour-manifesto-2024-ming-vase-strategy-policies-growth-net-zero/