Labour's problem is Labour's right

As Labour marks one hundred days in government, Labour’s problem is now very much the Labour right. A decline in government approval, the rapid collapse of the Prime Minister’s personal ratings, and poor performance in local government byelections all point to the same problem.

The economic and social policies and the methods of operating of the right wing of the wing of the Labour Party are being exposed, the self-inflicted cause of Labour’s difficulties.

Prior to the election, it was possible to see that the economic and political framework of the Labour leadership would run into trouble. Some of this was discussed in a post here on the night of the general election - in which it was argued that Labour’s economic framework will generate tensions and conflicts with its own base. It was an argument continued from one for Byline Times, that as long as Labour was in opposition there was a tendency to give the party the benefit of the doubt, and that the reality of the limitations of its economic policy would only be felt once the party was in office - where its programme and its weaknesses could be seen by the largest number of people for what they are.

Even so, satisfaction with Keir Starmer and his government has descended at remarkable speed.

The Labour Party conference this year was its first in government since 2009, but as it met in Liverpool the negative effects of Labour’s right wing course were being felt in the polls. YouGov polling published during the conference found that both the party’s and Keir Starmer's favourability ratings had fallen to a new post-election low. Labour’s net favourability was down from +1 after the election to -27 in September. Keir Starmer’s own ratings plunged from -3 to -30. Polling by Opinium conducted just before the conference had Keir Starmer’s approval rating at its lowest ever (-26%), down by 45 points from his first approval rating as prime minister (+19%).

A party’s conference is supposed to help a party’s standing with the public. But More In Common Polling published on 27 September had Keir Starmer’s approval at -27, described by Luke Tryl of More In Common as the ‘Starmer slide in approval’, which is ‘roughly the same level as Rishi Sunak was at when he called the election and a fall of 38 points since July.’

The collapse in Keir Starmer’s ratings has been huge and rapid.

Its cause is not chief of staff Sue Gray, who was set up to fail: it is driven by the public seeing and not liking the policy choices of the government.

In particular, the pensioners’ winter fuel payment has become an emblematic error. Rachel Reeves’s winter fuel payment cut has been disastrous for Labour’s standing. Asked by YouGov for the main or biggest reason that they feel let down, the cut to pensioners’ winter fuel payments came at the head of the list of top five answers: Winter Fuel Payments: 28%; Hitting pensioners / the poor: 16%; Wrong priorities: 13%; Not doing enough: 9%; Not keeping promises: 8%.

Labour voters were particularly likely to feel like they have been let down – 36% say they expected better. Winter fuel payments are working their way through the party, causing divisions in the Parliamentary Labour Party and amongst MSPs in the Scottish Parliament. Despite this, the Labour right has continued to defend the cut (and by default therefore to mobilise arguments that polemicise against universal provision).

The contrast between the donations received by the Prime Minister and others on one hand, and pensioners’ winter fuel payment cut on the other, is politically toxic, with one reinforcing the other. And Labour’s overall pitch, with warnings that things will first need to get worse before they get any better, is very well understood by people to mean that prospects for their living standards are not likely to improve soon. Although Labour has argued that it is ending austerity, its messaging has continued to talk relentlessly of tough choices. Starmer’s rhetoric at Labour conference – ‘so we will turn our collar up and face the storm’ – is a continuation of the ‘things will get worse’ message over the summer. In his conference speech, Starmer defined Labour’s approach as ‘a project that says to everyone – this will be tough in the short-term,’ warning that ‘I understand many of the decisions we must take will be unpopular.’ On the pensioners’ winter fuel payment, Starmer argued that ‘if this path were popular or easy we would have walked it already.’ If Labour says it enough times, it is necessary to hear it: the next period will be characterised by Labour’s ‘trade-offs’ and ‘tough decisions.’

Now, with the conference season at an end and with just one hundred days of the Labour government in office, the balance sheet is yet worse for Labour. The government and Keir Starmer’s approval ratings continue to tumble. Ipsos’ latest political tracker last week found Labour down from +6 net favourability rating when it was elected, to -21 now. Ipsos has Keir Starmer at his worst-ever favourability not just since the election but since he became leader of the Labour Party, with 52 per cent having an unfavourable view of him. YouGov polling at the start of this month also found Starmer was on his most unfavourable public standing since becoming Labour leader, with 63 per cent unfavourable and 27 per cent favourable. 60 per cent also had an unfavourable view of the Labour Party. Looked at a different way, Labour government approval also continues to decline, with the latest net score its lowest to date: approve, 18% (-10, vs mid-July), disapprove: 59% (+27). That is net -41.

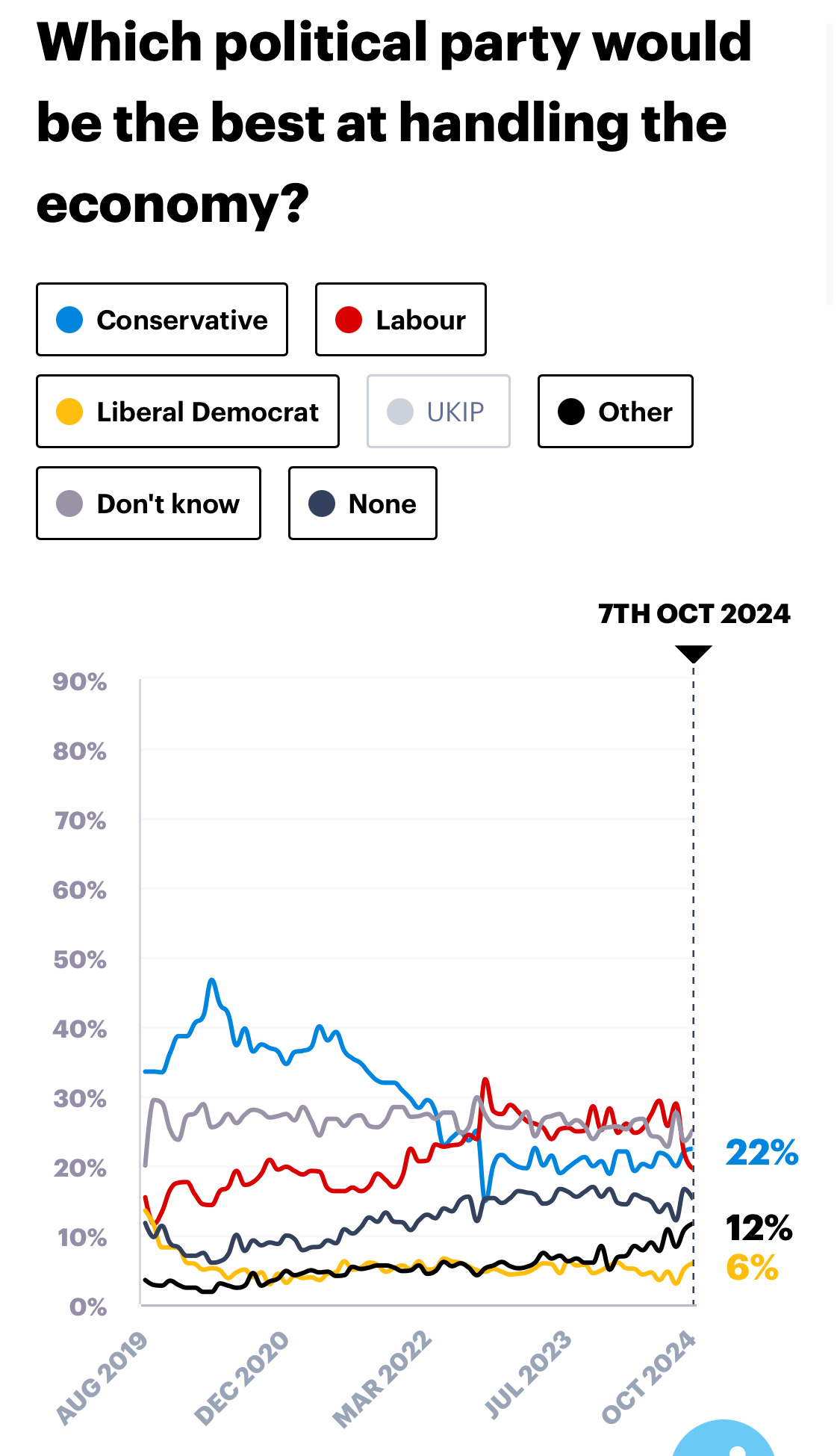

In one poll for More In Common, voters were slightly more likely to say they preferred the previous government under Rishi Sunak than the current government under Keir Starmer. At the end of September in YouGov’s monthly tracker on which party would be best for handling the economy, the Tories overtook Labour for the first time since September 2022.

Nor are Labour’s problems limited to polling of public opinion – they are also being realised at the ballot box. The net result of the last week’s council by-elections showed Labour sustaining four losses, and the Tories gaining four in total. Across all the council by-elections since the general election the results now stand at:

LAB: 30 (-13); CON: 22 (+8); LDM: 10 (=); GRN: 5 (+2); IND: 5 (-2); SNP: 4 (+3) RFM: 1 (+1); PLC: 1 (+1).

[Source: Election Maps UK].

Labour’s by-election downturn is actually worse than headline figures show, as can be seen in the results where the party’s vote share fell very sharply, despite holding onto seats.

Labour’s right is entirely responsible for the political course that is losing Labour support. However, the Labour right’s approach in this situation is of course not to stop but to keep going, to seek to solidify its position. That meant the first hundred days of Labour’s term in office descended into a briefing war at the top of the government over the position of the chief of staff, Sue Gray.

It is the height of political naivety to believe that Sue Gray was removed as the Prime Minister’s chief of staff because she has somehow an inferior skill-set for doing the job than the man who replaced her, Morgan McSweeney. Her ousting was a straight-forward political drive-by.

An assortment of reasons has been mobilised in briefings for why Sue Gray was not suitable for the job – such as about how rapidly she answered emails, or whose desk was located where, or how much she was paid compared to the Prime Minister, or the contractual position of some special advisers, or whether or not she was responsible for the government’s communications grid. All of these are not the actual reasons for her removal. They are there to provide a justification, whereas the reality was the campaign of the right wing circle around Morgan McSweeney for clear dominance.

A senior political team can be a mix of backgrounds and skills as long as each person respects the others’ roles and accepts the lines of authority, decision-making and accountability. In those circumstances a range of skills can raise everyone up. It is obvious that that situation did not apply in Keir Starmer’s operation. The ferocity of the media briefings by Gray’s opponents, even at the expense of how the Labour government was seen, made it absolutely clear exactly where things were going.

Gray was removed in a factional fight in which only one real faction existed - the winning one - around Morgan McSweeney. Gray herself did not have a base of supporters strong enough or willing enough to fight for her. Gray’s allies were not far from the truth when they described what happened as a coup – although it was not simply a coup against Gray but a successful move to consolidate the power of the right wing faction at the top of the Labour Party.

After Morgan McSweeney was removed as Keir Starmer’s chief of staff back in opposition, he was replaced by Sam White, whilst Morgan McSweeney was placed in the position of preparing for the general election. Sam White did not last very long. A search was undertaken to find a permanent replacement for Sam White, with Gray the headline-grabbing solution. However, as Labour was moving over onto election footing, most of the power within the party’s structures was with the election and party-facing functions, under McSweeney and with his fixers such as Matt Pound and Matt Faulding, and alongside key figures such as Pat McFadden. As is usually the case, the closer the election, the stronger the process in which election preparations subsume everything else. Thus even as Gray’s appointment was secured and announced the political weather in the leadership was being set by the group dominating election planning, including party management. Within the senior levels of the party there have been – and remain – many who have reservations and concerns, or are privately hostile to, the sharp right turn the party has taken. But there is no open fight or debate about it. Gray’s arrival as the chief of staff cast a spotlight on an internal culture which saw many shadow cabinet members treated as less favoured relations to other shadow cabinet members. Questions of whether some had adequate staff support arose; questions of why politicians were being by-passed started to be aired. Simply by not having come through the dominant faction Gray constituted a figure not wholly under their domination and their methods, providing an alternative mechanism for seeking to resolve internal tensions.

Go back to the stories once Sue Gray had taken up her position. Patrick Maguire of the Times found that ‘those who felt neglected by a party hierarchy whose divisions and mutual resentments are belied by Labour’s yawning lead in the polls, yearned for the arrival of the woman who once made the weather on Whitehall.’ Patrick Maguire reported that ‘it is with some relief that the grumblers relay two questions that Gray…has been asking at meetings where Labour’s biggest decisions are taken: where are the politicians? And where are the women?’ “She’s stressed the need to involve the shadow cabinet and their teams far more than was previously the case,” notes one source. She consults widely.’

Politico found similar dynamics at work. ‘She’s very kind, collegiate and empathetic and has got all those soft skills that people in politics don’t always have,’ one official told Politico. A shadow Cabinet minister described Gray as a ‘breath of fresh air.’ Another said that meetings had become more productive thanks to Gray’s ‘professionalism.’ The existence of such views was an inherent rebuke to the methodology of the McSweeney axis. According to Politico, ‘one Labour aide said they thought Gray would help Starmer’s top circle break away from its “Labour lads’ groupthink.”’

The political dynamic was set: there was absolutely no way this situation was going to be allowed to stand by the right wing circle around Keir Starmer, since it created a potential alternative decision-making mechanism. Gray’s cards were bound to be marked. Whether willingly or not, her presence represented a different channel for the resolution of political issues. The tension was masked by preparations for the election, because distinct roles could be understood – one around the election and one around post-election planning. But there were no circumstances in which the faction that has dominated the Starmer leadership and ridden roughshod over the party’s norms and structures was going to allow itself to be even marginally less powerful once in government. Therefore, the question was not whether a fight would break out, but when. In that fight, the chief of staff was hobbled from the start: if Starmer had wanted to invest his chief of staff with the authority to preside over a coherent Downing Street operation he would have made it clear that she was the principal adviser and that all other staff reported to her. But by not doing so, and having both Gray and McSweeney report to him, he sent a signal that weakened her status, including out into the public domain.

It has been said that Gray had to go because once an adviser becomes a story, they have to move on. But Gray was always a story, because of who she was, a very high-profile senior government civil servant recruited to the Opposition. Her position as a story was in fact part of the attraction of appointing her. The difference was that when Gray became the focus of an internal power struggle there was a conscious effort precisely to make the story about her in a negative sense, in order to remove her.

A key outcome of Gray’s replacement with McSweeney is to re-cement in formal terms the alliance between McSweeney and Pat McFadden at the Cabinet Office, who were at the core of Labour’s general election campaign. There is a seamless line of dominance by the Labour right across the key centres of power at the Treasury, Cabinet Office and Number 10.

Labour NEC member Abdi Duale gave a taste of the right’s mood at the Labour conference when he said that ‘if you have been waiting for a Labour government for fourteen years, and the first thing you do is vote against that government, you probably shouldn't be wearing a red rosette.’ A reference to the MPs who had voted to amend the Kings Speech to remove the two-child benefit cap, Duale’s remarks were an indication that the right will continue its intolerance of political forces to its left, regardless of how the party is performing. That means more conflict is coming over the Labour Party’s internal processes and selections as differences over policy emerge. In parliament the whips have told Labour MPs not to try to amend government Bills. On the ninety-ninth day of the government the Transport Secretary Louise Haigh was publicly undermined by Downing Street sources for standing up to the fire and hire practices of P&O.

But outside parliament the Labour right’s course has the effect of generating deeply conflicting responses. It has created the space for arguments to its left – as the vote at Labour conference on the Unite motion against the winter fuel payment cut, and in favour of a wealth tax, demonstrated. It is quite possible that this will grow. In the case of the situation in Gaza, mass mobilisations were large under the Tories and continue to be so under Labour.

But by failing to offer sufficient possibility of change Labour is also opening up space for the far and extreme right to move in.

It was not Sue Gray who chose to cut winter fuel payments or told people they faced tough choices, with things getting worse - the drivers of why Labour is marking 100 days in the doldrums. That fault lies with Keir Starmer, Rachel Reeves, and the Labour right at the top of the party. Gray’s removal was simply a further formal solidification of the Labour right’s dominance within the Labour government, and merely confirms that the course Labour was already on, which is going to be highly contested and not at all a return to political stability.